The horror genre requires a suspension of disbelief on the part of the viewer, asking them to compartmentalize the “real world” from their onscreen experience. Thus it would be worth noting a subgenre of horror that was able to instill or alter real-world belief systems, or at the very least chip away at the subconscious adherence to those beliefs. Certainly subgenres dealing with the supernatural would have an advantage to this effect in that their lore is part of our collective consciousness, yet there are only a handful of films dealing with witchcraft that take advantage of this predisposition to the extent that they bridge the schism between modern skepticism and endemic credulity. Perhaps then such films are able to open pathways in our mind that have been restricted by the societal pressure to repress imagination and receptiveness to the preternatural as we “mature” towards adulthood.

Raul Artigot’s El Monte De Las Brujas (1971 AKA Witches Mountain) imparts a hypnotic sense of place with its ethereal location shooting in various Madrilean and Austurian sites, most notably the title accursed mountain in the remote Picos de Europa, a region previously photographed by Artigot for documentaries and peppered with ancient stone cottages. In this setting a witches coven is presented as an organic means of survival for women who are self-sustaining, choosing to be free of the burden of patriarchal male dominance. In fact, this is the only film on the subject that answers the question as to how women can survive and reproduce outside of the family structure in the absence of a traditional heterosexual relationship. This is much to the dismay of the caterpillar-moustached photographer Mario (Cihanger Gaffari) who thinks he has found paydirt in the impromptu companionship of the charismatic and glamorous Delia (Patty Shepard). These heady themes of male chastity and bondage are set against historically referenced witch practices along with an oppressively distorted and repetitious Latin choral chant. The expected hookup between our macho protagonist and his chaste companion Delia is fractured by a final frame visual punchline that serves as a cold shower to men who regard a woman’s beauty as something to be dominated. Ironically, due to reports of women dancing naked during an exterior nighttime shoot, production on Witches Mountain was temporarily shut down. As a result of the controversy in Franco’s Spain, the film was blacklisted, never showing in its native country but somehow exported to US television in edited, cropped and dubbed form in 1975 as part of Avco Embassy’s Nightmare Theatre syndication package. It received a special mention at the Sitges International Film Festival where it was viewed by the jury but could not be screened for the public due to the blacklist, thus the only known public viewing of the film was its US television broadcast, leaving one to wonder if the film was indeed too close to its subject matter for comfort.

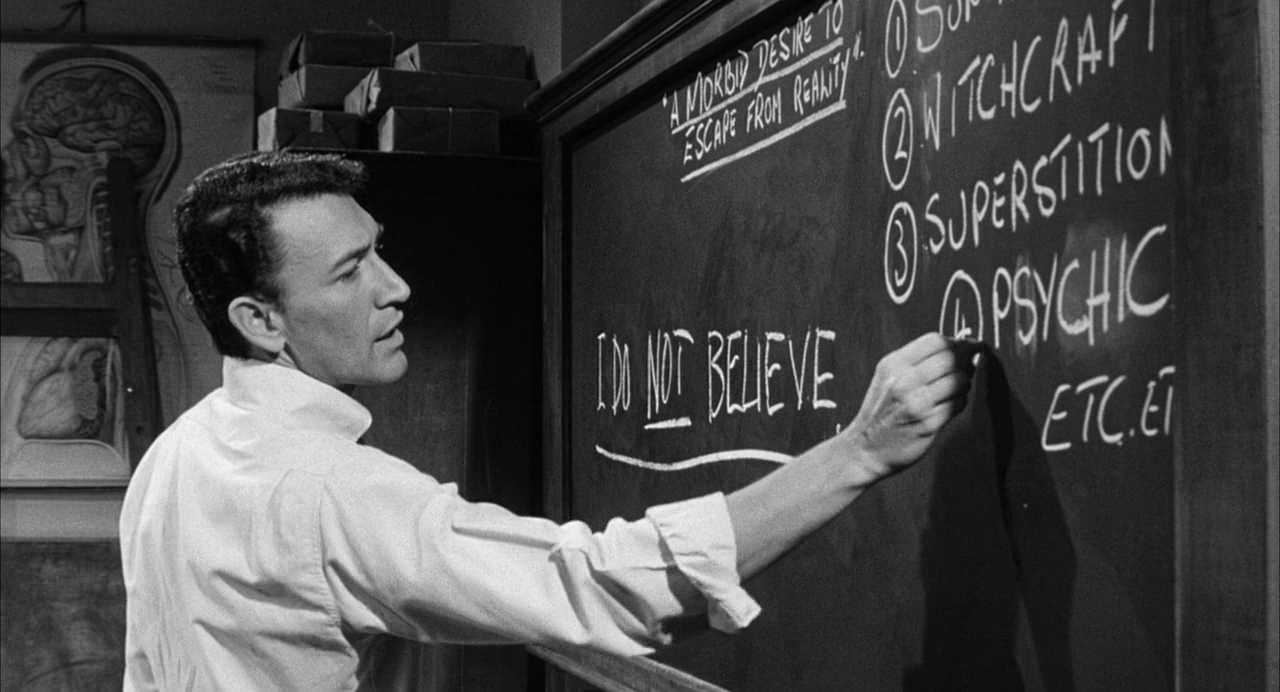

Two early 1960s British films, City of the Dead (1960 AKA Horror Hotel) and Night of the Eagle (1961 AKA Burn Witch Burn), steep their pre-emptive skepticism of witchcraft in academia, the university professor Norman Taylor in John Llewewlyn Moxy’s Night of the Eagle married to wife so protective she practices witchcraft, while Christopher Lee’s wryly sinister Professor Driscoll sends his lily white student Nan Barlow to the remote, fog-shrouded village of Whitewood to complete her research paper on witchcraft in New England. The marital conflict in Night of the Eagle reveals a patriarchy in husband Taylor that is as unimaginative as it is domineering, ignoring the inevitable truth that he has become targeted by a witch and instead ordering his wife to destroy the artifacts that serve as his only protection. As Taylor tries to apply establishment logic in order to dispel the notion that it is witchcraft causing his downward spiral, the viewer’s skepticism is vicariously whittled away as the power of suggestion imposes a slow burn of doubt transitioning into a frenzied subjectification of horrific imagery. It is the questioning of male-dominated society and its ownership of female identity, as well as superstition and its interplay with traditional gender roles, at the core of Night of the Eagle that has the power to alter established belief systems in this world as well as the next.

While also rooted in academia, City of the Dead capitalizes on the tension between communal mores and intrusive outsiders by having Nan travel to a town shrouded in perpetual darkness and swirling fog, a refuge from the purified world inhabited by shrouded figures and specters of a violent past. The film recalls the best of the Val Lewton RKO horrors of the 1940s, making the most of its meager budget to compose a classical brand of atmospheric dread aided in no small part by Desmond Dickinson’s evocative black and white photography which makes the most of its minimalist studio bound elements. As Nan makes the journey from the sunlight corridors of her university to the fetid, forgotten corner of New England known as Whitewood, it becomes clear that we are in a different dimension entirely. It becomes difficult to discern if the melancholic repression of the witches who populate the town is more disquieting than their potential for inflicting pain through black magic. In a scene that crystallizes the oddly compelling effect of the film, Nan is invited to a dance at the lobby of the Whitewood’s only inn, the music and merriment only starting when she shows up to the affair and abruptly ending as soon as she returns to her room. Her realization of the precipitous solitude and that this happens to be Candlemas Eve, one of the two favored nights for the witch’s Sabbath, imparts a sense of dread as chilling as the iconic horror visions of shrouded still figures in the mist staring at her from afar. The subtext of Nan traveling to a place that has served as a cistern of deviant sexual behavior under Driscoll’s seductive spell and ultimately meeting with fiends of historical proportions is not at all lost on director Moxy, who climaxes her shocking confrontation with the cult with a revelation of the dangers of such seduction real or imaginary.

In addition to showcasing well-researched and traditional means and methods of the art of witchcraft, these four films reveal differing approaches in conveying the motivations and magical power that witchcraft is associated with. In Witches Mountain, it is the self-reflexive nature of exceptionally rugged production conditions punctuated by a convergence of unsettling atmospheres that organically conveys a preternatural existence. It is the frustration engendered by the stifling nature of the traditional marital power structure and how that structure obviates belief in the supernatural goings on that are obvious to the audience that fuels the escalation of horror in Burn Witch Burn. City of the Dead upends conventional narrative structure accentuating the disorienting effect of a claustrophobic and deliberate mise en scene. The disparate methods employed by these three films in conveying the archetypal liberation of witches is a testament to the leverage of the horror genre over others in its ability to penetrate the veneer of learned adult skepticism ensuring the significance of witches as powerful icons in social psychic development.

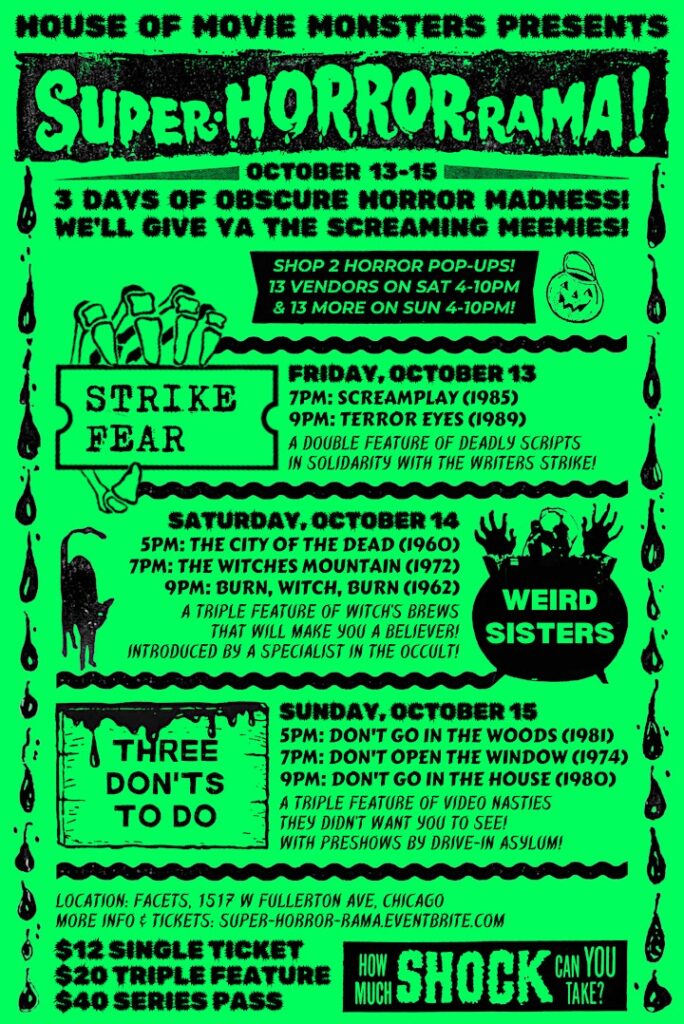

SUPER-HORROR-RAMA! Tickets, Fri, Oct 13, 2023 at 5:00 PM | Eventbrite