Toho’s original Godzilla (1954) is not only one of the most impactful monster movies of all time, it’s one of the most potent post-war cautionary tales in cinema history. Due to its proximity to the mass death and destruction inflicted upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the US in 1945, Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla pulls no punches in its metaphorical depictions of the horrors of nuclear war. It does so through a combination of Eiji Tsuburaya’s stark and deliberate black and white special effects photography, moody scenes of destruction set to Akira Ifukube’s funereal dirge, and its central ethical tension between man’s jekyll and hyde penchant for self-destruction versus his instinct to preserve humanity. The human tragedy plays on a global scale parallel to the trajectory of the monster destruction, both always reminding the audience of the potential for escalation towards destruction of the planet.

While the original Godzilla is admittedly a tough act to follow, Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One fails miserably to acknowledge or duplicate the powerful formula of Honda’s original or many of his sequels. Tenacious in its repetition of maudlin western-based blockbuster formula romance and last-minute heroics, the film’s lack of interest in seriously addressing any of the issues it grandstands about is manifest in limiting the protagonist’s preoccupation with resolving his own personal war, an intentional decision consistent with the film’s prioritization of histrionic melodrama and counterfeit science over any universal implications. To assure that we are adequately informed of the film’s central conflict, Koichi (Kamiki Ryunosuke) tells us repeatedly that before moving on with his personal life he must emerge victorious in “my war.” His war stems from the fact that as a kamikaze pilot Koichi faked a technical problem with his plane and gruff technician Tachibana (well played by Munetaka Aoki) got wise to his abandonment of the mission, but only just before a fledgling Godzilla came ashore and wiped out the entire island crew.

This opening scene with Godzilla unspectacularly picking up humans with his teeth and throwing them like ragdolls into the night diffuses any potential build to Godzilla’s appearance while instantly demystifying the entire film. The introduction of Godzilla in the original is ominous because the monster first appears during a typhoon, barely indistinguishable from the natural forces of the storm itself and only shown in fleeting closeups that intentionally avoid revealing the form of the creature. Minus One’s botched opening is the first indication that there will be no sense of mystery or dread in Takashi’s film, any tension subverted by the compulsion to resort to blockbuster tropes and overexplained exposition. Godzilla is portrayed as a Jurassic Park-style dinosaur, crouching and puffing his chest, sticking his head out forward and roaring, and snapping up humans in reptilian fashion. Perhaps due to the limitations of CGI, he seems more animalistic than monstrous, offering none of the connection or sense of the unreal afforded by a man in a suit. It’s no coincidence that the closest the film comes to capturing the essence of Godzilla is in the half-moon eyed sculpted mock-up head used for close-up swimming scenes.

Koichi’s failure to fulfill his kamikaze assignment is only one of a series of missteps that escalate to make his character more inept than sympathetic. His failure to shoot Godzilla under Tachibana’s orders while he is sitting in a cockpit with a Rifle Caliber Machine Gun gun aimed squarely at the approaching beast indicates he either needs a trip to Oz for a spot of courage or that we are moving into Jerry Lewis territory. While his avoidance of a kamikaze mission is understandable, his subsequent actions are not borne of human emotion but of screenwriter contrivance, primarily so that Koichi can experience some “personal” conflict with Godzilla that would need to be resolved through climactic heroics. This run-of-the-mill personal grudge motivation trivializes the primary conflict to a character who does inexplicably follish things, and one who does not adopt a position regarding war any broader than the indulgence of his own personal failings, going up against a massive and powerful radioactive monster in order to exorcise his personal demons. Not exactly a fair fight, nor a particularly inspired one that offers any reflection on war or nuclear escalation.

In fact, the whole film seems to be scrubbed of any authentic depiction of or reference to the horrors of war in general or the impacts of nuclear war in the case of Japan in 1946. During this period the US was occupying Japan, their jeeps buzzing in the streets to the point of US soldiers literally directing traffic. Ironically, the occupying forces heavily censored Japanese entertainment, press and public assembly to the point of putting down a lobor strike at Toho in 1948. So to those who marvel at the period detail understand it is as sanitized of the rest of the film, substituting a naive brand of patriotism as if the occupying forces were still exerting their influence ordering Yamazaki not to include any authentic portrayal of historical context. At the film’s outset we see Koichi and his adopted family living amidst ruins, but there is nary a mention of Hiroshima, Nagasaki or the atom bomb apart from a 30 second newsreel style snippet alluding to nuclear testing at the Bikini Atoll. This skirting of the issue that was both literally and figuratively at the core of the original Godzilla makes Takashi’s film just another casualty of commerce over art. If the original 1954 Godzilla had to be pasteurized and Americanized in post-production to make it palatable for consumption by domestic audiences upon its release in 1956, Godzilla Minus One appears to have been neutered into political expediency in its pre-production stages, capitulating to the western cancer capitalism that is called out in showa era films like King Kong vs Godzilla (1962) and Godzilla vs Mothra (1964).

It is telling that a Japanese Godzilla film must ascribe to international capitalist and consumer standards in order to be acceptable to the establishment and qualify as the next feel-good blockbuster as box-office receipts from the decidedly more frank Shin Godzilla (2016) suggest. Shin Godzilla was a box office hit in Japan grossing $75 million, but barely hit $2 million in the US. The film’s portrayal of the US as a militaristic bully made it controversial in the US, while in Japan this truth and its pointed satirizing of the multi-leveled Japanese governmental bureaucracy connected with audiences. Minus One avoids anything remotely controversial by substituting soap-opera melodramatics as “serious” content. softened with an upbeat ending that defies every law of science and screenplay writing. Yamazaki’s impossibly cornball final scene is reminiscent of US distributor Terry Morse’s substitution of the line “The whole world could wake up and live again” over the Japanese version’s “But, if we keep on conducting nuclear tests, it’s possible that another Gojira might appear somewhere in the world again” as the original 1954 film’s final words so as not to challenge US nationalist pro-bomb fervor. Far sadder than Minus One’s by-the-numbers faux romantic blockbuster conclusion is its capping of all that has gone before in the film as completely irrelevant, including Godzilla himself.

I say that because not only is the film laughable in its dirty trick of summing things up in such a tidy fashion by having a character survive a blast wave generated by Godzilla’s atomic breath, but because it trivializes the devastating direct effects of an atomic explosion for mere narrative convenience. And it reduces perhaps the most shocking scene in the film, the apparently definitive death of Noriko as she is blown into oblivion by 300 mile an hour nuclear winds, to an embarrassing feel-good moment. Can one imagine Dr Serizawa surfacing at the conclusion of the original Godzilla, smiling blithely at the camera bathed in sunlight as treacly piano music litters the soundtrack? Of course not. An added insult is the randomness of someone beckoning Koichi to a hospital where Noriko has conveniently been sequestered away for half the film, yet another narrative cheat and a wonderful coincidence that she would be discovered the moment Godzilla is defeated. And the execution of the scene, Noriko smiling in the most saccharine manner at the sight of a very awkwardly sobbing Koichi entering her hospital room, is not only trite but comical as a head-on atomic blast has left her only with a gauze bandage wrapped around her head. While the scene is unsalvageable, in light of its impossibility it might have been more effective if the tragedy that both had suffered would have resulted in expressions more thoughtful than the final freeze frame of an episode of an Aaron Spelling television series (Charlie’s Angels or The Love Boat take your pick).

With expectations for screenwriting currently at a historic all-time low there are moments in Godzilla Minus One that prove how we have been conditioned to abandon critical thinking in order to take one more turn on the cinematic roller coaster ride. When Koichi is forced into taking a “dangerous” job detonating mines left in the ocean by the US (depicted more like shooting tin cans off the fence in the backyard), he meets a ragtag group of stereotypical outcasts including an Einstein-like Oppenheimer reject with round glasses (Kenji), the big silent strong guy who eventually is cajoled to nod his head and smile, and the uncertain cowardly kid who finds inspiration in Koichi’s plight. Inexplicably, none of Kenji’s mine-hunting shipmates are aware he is a scientific genius until he makes his tortuous formal presentation of how to get rid of Godzilla. Of course, the content of his plan shows that he is hardly all that, but the casual convenience of his character’s “genius” is emblematic of the writers’ assumption that the spectacle will effectively supplant critical thinking. After Godzilla’s destruction of Ginza, Kenji is asked if Godzilla is going to return and responds that “10 days” is what he would expect, a completely random response which serves as a device to generate suspense as the men work to return the airplane in this time frame. Throughout the film, characters meet up in the most chaotic of scenes with no explanation, the most egregious being Koichi’s discovery of Noriko amidst the chaos after Godzilla’s train-bite redux.

The film blends monster-on-the-loose formulaics with elements from recent US boxoffice hits to numbing effect. The most egregious is the completely superfluous yet extended presentation by Kenji (Yoshioka Hidetaka) of his loony plan to destroy Godzilla. Surrounding Godzilla with freon bubbles to make him descend to the bottom of the ocean so that the pressure exerted by the depths will crush him is not only more farfetched than Plan Z in Gamera (that would be luring Gamera to an energy source inside a giant rocket and blasting him into space), it is complete contrivance as where precisely would a dinosaur awakened by H bomb testing originate? The bottom of the ocean of course. Just in case that doesn’t work, they will also surround him with balloons that look like a ring of fanny packs to bring him up from the depths hoping that rapid the change in pressure will somehow do him in. Except as the film shows to excess Godzilla is quite agile in the water whether it’s emerging, doing the breast- stroke, or diving, so why any of the naval experts watching would give this the go ahead is baffling, just more contrivance so Kenji can say something profound about using Godzilla’s habitat against him. It is also worth noting that while the Oxygen Destroyer of the original film had multilayered implications to man’s penchant for scientific achievement and destructive power, Kenji’s plan is utterly meaningless on a broader scale. It is just another dubious plan to rid the world of imminent destruction as seen in any variety of more authentic 1950s sci-fi films.

Koichi’s scheme to kill Godzilla by flying a bomber into his mouth exemplifies the film’s disregard for internal logic. Earlier in the film, Godzilla swims after the mine-hunting crew’s ship and the mine squad devises a plan to detonate one of the mines in Godzilla’s mouth. When it explodes we clearly see part of Godzilla’s head disintegrate and then instantly regenerate as if there were no impact at all. So why wouldn’t all the men including Koichi be aware that flying a bomber into Godzilla’s mouth would have the same effect? Why when he presents the plan doesn’t somebody say “oh yeah remember that mine thing didn’t go so well?” More puzzling is why all the critics raving about the film fail to notice that the plans to rid the world of Godzilla which take up so much of the film’s running time are far more illogical than anything presented in those “cheesy” old Godzilla movies.

The exposition detailing the execution of Kenji’s plan, replete with massive warships bumping against each other (?) to somehow wrap Godzilla in freon jets and balloons, also turns out to be of absolutely no consequence. This “bobbing for Godzilla” silliness fails of course, but not before we are roused to a knowing cheer over the sight of the cowardly Shiro and his merry band of tugboat toters coming to the rescue. It’s one of those inspirational last-minute potential “rescues,” the sort of which is a dime a dozen in any American action or sci-fi blockbuster and serves no purpose apart from bringing together that merry band of mine-hunting misfits for a final bow. When what has already been telegraphed as the real end of Godzilla ultimately comes to pass, Koichi flies a massive bomber at high speed into Godzilla’s mouth a split second before Godzilla blasts all the ineffectual naval vessels to smithereens…and the plane just hangs from Godzilla’s mouth like a giant cigar. When the speeding plane hits Godzilla, it has no kinetic impact whatsoever and when it explodes Godzilla crumbles away as if he were made of stone. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to reveal that what we knew would happen does indeed transpire in the predictable final image which anticipates Godzilla Plus One.

Even attempts at recalling scenes from the original Godzilla, which are by default the film’s best moments, are diminished by the film’s technocratic approach. An exciting moment when Godzilla does his train biting routine turns into the requisite high and dizzy for Noriko as she hangs from the open end of a half-eaten train car, only to fall gingerly into a pool of water below. Godzilla’s first (and only) appearance on land is accompanied by Akira Ifukube’s original score, a powerful theme which evokes a Pavlovian response from seasoned Godzilla fans. But instead of Godzilla looming in the darkness, we have him trouncing in broad daylight, his iconic theme generating the emotion while the routine CGI creature rides Ifukube’s coattails. Hearing the deep, pounding strains of Ifukube’s score just serves as a reminder as to how unremarkable Sato Naoki’s monster muzak is in this context. It’s pleasant enough in itself, but its mix is more apropos to new age romance than monster destruction. The most effective nod to the original is the redux of the reporters covering Godzilla’s rampage becoming victims of their duty. But in the original film, the reporters were in a much more precarious situation, on a tower platform, and it was the flashbulbs in the night that attracted Godzilla’s attention as he came directly towards them. Yamazaki has the reporters on top of a building in broad daylight watching Godzilla walk by parallel to their position, offering the reporters ample chance to escape. The originals brilliantly conceived subjective shot from the reporters’ point of view as the tower fell to the ground is replicated here but its impact certainly not duplicated.

While Minus One is largely a product of hype and the advent of entertainment as consumption, it is encouraging to see the king of the monsters garnering positive attention and perhaps widening his already ubiquitous appeal. It’s a relief not to see Godzilla being mocked for post-production dubbing or because you can “see the wires” (moreso today in the face of the double-edged sword of 4K restorations). And of course as a seller and collector of everything Godzilla for the past 45 years having the Big G in the limelight is certainly good for business and collecting. Unfortunately, I am unable to share in the celebration of Godzilla Minus One although admittedly it is preferable to, although often uncomfortably similar to, the American Legendary Pictures commodity. Shin Godzilla was at least serious in its contemplation of the re-militarization of Japan, hopeless governmental bureaucracy and the dangers of US military adventurism, even if like Godzilla Minus One it should have been shorn of 30 minutes of exposition in favor of 10 more minutes of Godzilla. Shin’s rapid-fire banter and roving camera brought new energy to the series while honoring Godzilla’s historical relevance. There was evidence of a creative vision and if the film was cynical it was so towards its designated targets and not the audience or the character of Godzilla. Minus One fails to take advantage of its opportunity to warn current Japanese leadership regarding their alarming move towards remilitarization.

In fact Godzilla Minus One is missing any sense of gravity at all, Godzilla himself showing far too much weight while the film has none. It’s yet another casualty of the mind-snatching entertainment-as-consumption industry, conditioning its subjects to embrace media which exists to keep them on the hook as long as possible through melodramatic story arcs that lead to nowhere until the 10th season. Godzilla Minus One is a microcosm of this industry, paying considerable attention to the most obvious technical aspects of production, which is certainly a credit to auteur Takashi, but constructing its story and setpieces with precision as clinical as a software developer for Facebook or YouTube working to keep their mesmerized minions scrolling on their precious devices. All the proper buttons for dedicated blockbuster appeal are properly pushed, from the rogue naval rejects banding together to enact the stupidest of plans to the absurd return of the reclusive and gruff airplane technician who turns out to have a heart of gold to the contrivances–including a flashback reveal worthy of the worst of the streaming binge-fests–that assure none of the main characters will actually die.

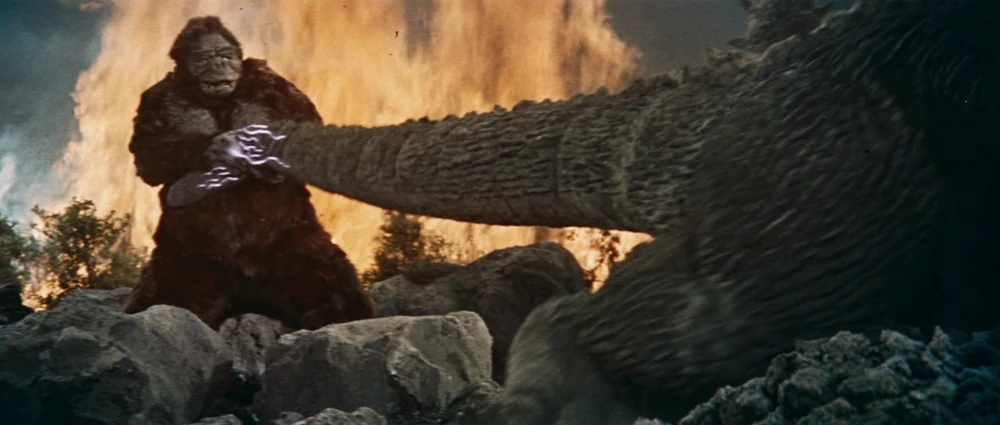

The Japanese version of King Kong vs Godzilla (1962) serves as a serio-comic satire of the cancer capitalism that infiltrated post-occupation Japan’s economic prosperity using giant monsters as its Abbott and Costello to soften the blow. What it lacks in consistency it makes up in manic conviction and authenticity.

Godzilla Minus One is an imposter, a sanitized and slick slice of pasteurized movie product that betrays Godzilla’s origins while purporting to be anti-war. Its overwrought Hallmark Channel melodramatics could only succeed with an audience awash in marketing delivered through the persuasive power of social media, convincing millions by inundating the subconscious with a continuous stream of hyperbole delivered in 15 second snippets telegraphing the film’s dramatic impact, relevance and superiority to other Godzilla films. So why should I be surprised at the uniformity of over-the-top responses parroting the studio-generated bullet points that filled my social media feed for months prior to the film’s realease? Breathless exultations of the most enthralling “human drama” to be seen in any Godzilla. Widespread declarations of Minus One being the “best film in the Godzilla series” saturated every Godzilla group on social media and sponsored posts well before anyone in the US could have seen it. The hype machine utilized its weapons of mass deception in unprecedented fashion on me and anyone who had even a passing interest in Godzilla, so much so that between one visually exciting destruction scene and a naive strain of “let’s put on a show” nationalism millions are convinced the film is some sort of powerful masterpiece while they cannot resist putting down what are considered lesser Godzilla films in the series. If the consequence of lionizing junk technology media like Minus One might be limited to the progressive catatonic state of its audience, could the contagion of conglomeratized groupthink bleed into the understanding or lack thereof regarding urgent issues of war and peace in the real world? It seems that films of self-proclaimed import like Minus One that play pretend with history augment a pervasive ignorance of historical context that enables militarism and imperialism in lieu of cautioning against it. In this manner and in its fetishizing of war machines Minus One goes against the overarching message of the Godzilla series, making its pretense as some sort of anti-war film particularly toxic.

I would argue that a film that is reviled like All Monsters Attack/Godzilla’s Revenge (1969) holds more intrinsic value and is far more loyal to the cautionary origins of Godzilla than a plagiaristic digital vessel of commoditization like Minus One. Considered to be the worst film in the Godzilla series (along with Godzilla vs Megalon (1973)), Godzilla’s Revenge (1969) was aimed squarely at the kiddie audience Toho had been courting for several years. But in its bleak and barren industrial landscapes and frank depiction of the toll Japan’s industrialization was taking on the working class much of the film adopts an incongruously realistic tone. Its central conflict involves 10 year-old Ichiro and his struggle to survive the dual threat posed by grade-school bully Gabara and the terminal absence of his working-class parents. The film is sympathetic to Ichiro’s plight, effectively delineating the reasons he needs to escape to the closet where he keeps the makeshift headgear which transports him to Monster Island. There he finds escape and meets up with Minya who is being bullied by his own Gabora and can change from kid size to monster size in a matter of seconds. Ichiro uses his noggin’ to help Minya to defeat monster Gabora which ultimately leads to him conquering his own real-life Gabora, but not before becoming a local hero by nabbing two on the lam gangsters. Honda shows sensitivity in his direction of children and has referred to this film as one of his favorites. It is a kindhearted film, promoting awareness of the loneliness faced by a generation of latchey kids in Japan while offering solace for kids who are bullied. I understand the reason Honda considers it a favorite as it’s an altruistic use of Godzilla in defense of children, something adults should be able understand despite the stock footage and Ichiro’s purportedly offensive short shorts.

It is something of an auteur accomplishment for Yamazaki to produce a film that is so technically polished for $15 million, but give me a few million and I can hire enough digital artists and technicians to craft a couple of impressive monster scenes. That’s honestly not much of an achievement these days, akin to making monsters using the latest app. Yamazaki uses the technology of the day to his advantage but as a filmmaker he has no discernible personal vision, visual flair or understanding of composition. I would argue that most of the films in the Showa series are more carefully crafted, more imaginative and far more visually innovative than the expediently westernized mise in scene that dominates Minus One. And while the original Godzilla series suffered from declining production values into the late 1960s and early 1970s, none of the films were so by-the-numbers they felt like they were generated by AI. Certainly no entry in the Showa series could have be mistaken for an American production, yet Minus One looks as if it could have been produced by any major American studio and directed by any of the American delegators of Marvel/Mission Impossible/Godzilla/James bond banality. Perhaps that’s why it’s a boxoffice hit in the US, repeating the history of the Americanization of the original Godzilla which was the most successful Japanese film in the US up to that moment. It’s a film that Godzilla fans can take their non-Godzilla fan friends to and not be judged, a Godzilla film for those who are less open to “traditional” kaiju films and one that is patently inoffensive to Americans but quite offensive to anyone who cares about history. My introduction to kaiju films for kaiju skeptic friends has been any of Daiei’s trilogy of 1990s Gamera adventures, dramatically sound films that combine suitmation and CGI seamlessly. These films and the Showa Godzilla titles exemplify the essence of kaiju cinema, which is largely defined by physical entities like a man in a suit, puppets or marionettes being used to represent monsters marauding within a universe possessing its own internal logic and often contemplating a broader relevance. This madcap combination is the soul of kaiju cinema in evoking an overwhelming sense of the fantastic, often maximally appreciated through the suspension of disbelief but not requiring the suspension of thought. As a disposable by-product of today’s consumer entertainment complex, Godzilla Minus One meets expectations. As a Godzilla film possessing any integrity or any lasting cultural, historical or artistic relevance, Godzilla Minus One equals zero.

2 responses to “Godzilla Minus One Very Important Thing”

AMEN! Minus One will go down as one of the single most overrated films ever, monster, drama, science fiction, what have you. I know we Americans cannot make Godzilla, it’s a shame to now see the Japanese can’t make him either.

Thank you for offering some reassurance that the whole universe and Godzilla community has not succumbed to hype and mediocrity. Obviously I too am in shock regarding the hyperbolic enthusiasm for what is genuinely a mediocre film at best.