SCHEDULE AND TICKETS FOR “DINOSAURS PLUS! ON FILM AT DOC FILMS Saturday 1 (docfilms.org)

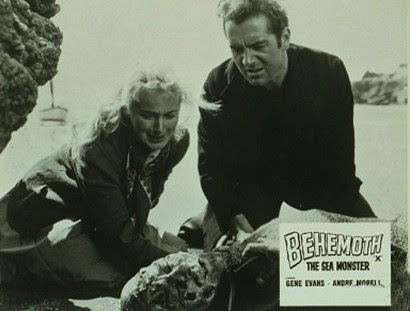

My frustrations about the milquetoast blockbuster duplicity of the latest Godzilla film were unexpectedly mitigated by a welcome screening of Eugene Lourie’s shoestring dinosaur-on-the-loose entry The Giant Behemoth (1958) as part of the Brothers Valauskas “Dinosaurs Plus! On Film” series screening at DOC Films at The University of Chicago. It had been 15 years since I’d seen this film, and viewing it on a truly big screen in the wake of Minus One’s compulsory reception reinforced my appreciation of smaller science-fiction films with larger aspirations. Lourie’s film follows the formula of his previous stop-motion dinosaur hit Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) with the significant exception that his updated version is much more adamant and explicit in its statement against the trend towards nuclear testing and proliferation. There are multiple scenes of victims of the Behemoth, the creature emitting visible radiation while suffering from a meltdown process, dying from radiation burns holding their charred faces screaming through the streets. Lourie’s screenplay is refreshingly conscious of the plight of the fishing village where thousands of dead fish wash ashore suffering the direct economic impact of the war industry, even to the point of showing named species of fish lighting up with radiation under radiographic testing in a scene exceptionally scientific for a low-budget monster movie. The method of dispensing with the behemoth could be seen as belying the film’s message, but it does suggest that the only way to deal with the deadly effects of nuclear weapons is with nuclear escalation. And the film’s final dystopian punch leaves no doubt that this is as much as cautionary tale as a monster movie.

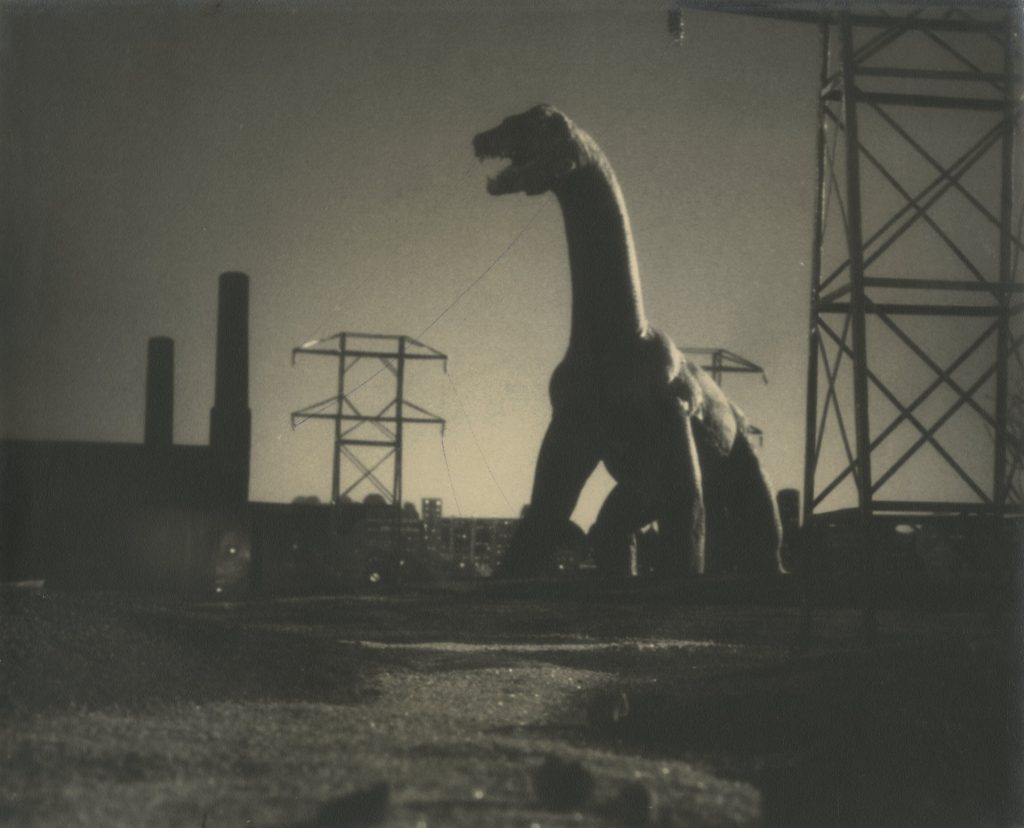

It was surprising to see how such a small, relatively minor sci-fi film had the mettle to push the boundaries of the genre to make its point. The production was hampered by a budget so low that a now infamous stiff (but well-sculpted) mockup head had to be used for repeated shots of the dinosaur’s head rising out of the Thames, and Willis O’Brien and Pete Peterson were forced to shoot most of the animation scenes on a tabletop in Peterson’s garage. Still the stop-motion footage is dynamic considering the absence of a designated studio, O’Brien and Peterson utilizing much of the same perspective O’Brien employed in King Kong (1933) with the behemoth rushing towards the audience filling the screen with crumbling structures. Perhaps out of necessity, the buildup to the appearance of the behemoth makes its rampage all the more exciting, even if the execution is a bit reminiscent of the stiff walking motion of the brontosaurus in O’Brien’s pioneering Lost World (1925) (which is also on the schedule in the “Dinosaurs Plus!” series). For all of its shortcomings, The Giant Behemoth stands out a visually striking example of the subgenre, as satisfying in its utilization of real science to reinforce its anti-nuke stance as it is in its more spectacular monster-on-the-loose aspirations.

It’s no coincidence that four of the nine films on the series docket are Godzilla films, three which are rarely if ever screened theatrically. Godzilla Raids Again (1955) was not close to achieving the impact of its progenitor, but it does feature excellent black and white effects photography and the first authentic kaiju battle with the introduction of the ankylosaurus-like Anguirus. It is reminiscent of Godzilla Minus One in eschewing cultural relevance for romantic drama, adopting a tone that is jarringly different from that of its grim and dark predecessor. It’s unfortunate that one of Tsuburaya’s camera operators filmed the effects footage at the wrong speed, resulting in some of the battle being sped up as in slinet film comedy. But as a monster film it is historic as well as satisfying, and it certainly does not skimp of the monster action as newer Toho productions do. Godzilla Raids Again will be paired with Winsor McCay’s pioneering animated short Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), the first animated film to use naturalistic techniques that would influence the work of Max Fleischer and Walt Disney among others.

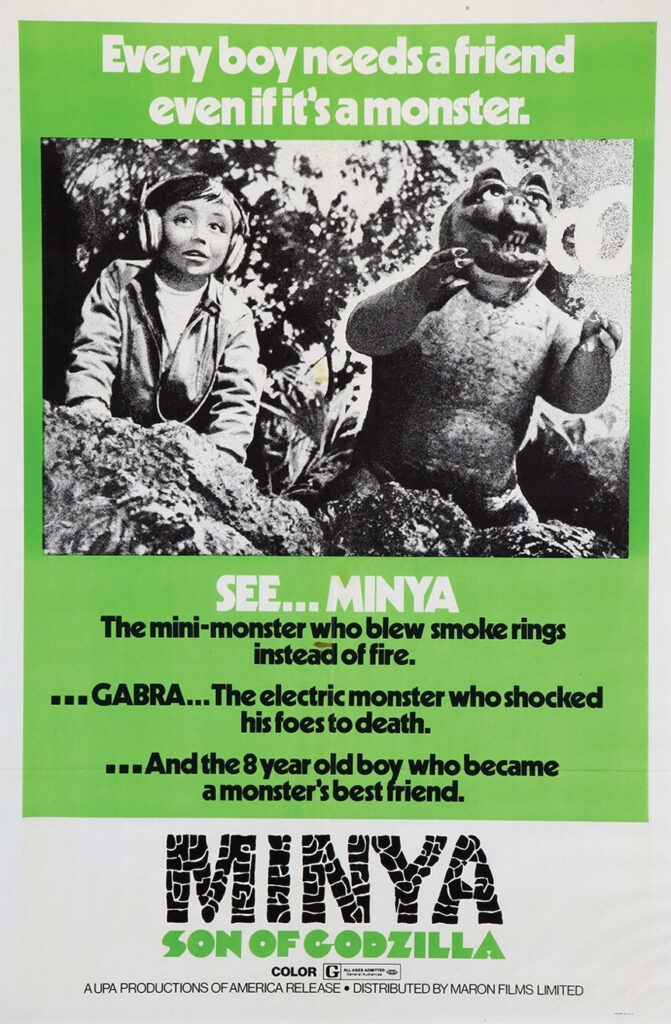

Two of the Godzilla films being screened are largely dismissed because they are aimed squarely at children, although I would argue that Son of Godzilla is less a kiddie film than a jungle sci-fi adventure featuring a “cute” monster in Minya. Much of the film is endearing in its depiction of Godzilla nurturing his newborn son while at the same time offering tough love in fostering independence. One of my favorite moments in any Godzilla film is when “dad” instructs his son on the finer points of defense, in this case a lesson in producing a ray of atomic breath in lieu of smoke rings. The scientific considerations are prescient although not fully developed. A group of scientists conduct experiments on remote Sollgel island in order to control the weather in anticipation of dwindling food supplies on earth with the unexpected effect of mutating the local population of mantises and spiders into giants. The depiction of the giant mantises known as Kamakirus and the giant spider Kumonga are impressive in their fanciful and ambitious use of puppetry, the menacing bugs controlled in complex fashion by piano wires from above adding to an audacious vision of fantasy accentuated by bright red bubbling swamps and prehistoric-styled vistas.

Son of Godzilla embodies the singular vision of the authentic Godzilla series, directed by Jun Fukuda in a more histrionic and upbeat fashion than Honda while maintaining the sense of enchantment characterizing much of Toho’s fantasy output. To this end the film’s final moments speak to the audacity, charm and gentle nature of the Godzilla series in the 1960s. Godzilla and Minya are forced into hibernation by a manmade tropical winter, the only sound being Godzilla shuffling through the snow to retrieve an immobilized Minya, pulling him close to offer warmth for their impending hibernation.

The second “kiddie film” in the series All Monsters Attack (1969)(AKA Godzilla’s Revenge) is widely onsidered to be the worst film in the Godzilla series, but in its bleak and barren industrial landscapes and frank depiction of the toll Japan’s industrialization was taking on the working class much of the film adopts an incongruously realistic tone. Its central conflict involves 10 year-old Ichiro and his struggle to survive the dual threat posed by grade-school bully Gabara and the terminal absence of his working-class parents. The film is sympathetic to Ichiro’s plight, effectively delineating the reasons he needs to escape to the closet where he keeps the makeshift headgear which transports him to Monster Island. There he finds escape and meets up with Minya who is being bullied by his own Gabora and can change from kid size to monster size in a matter of seconds. Ichiro uses his noggin’ to help Minya to defeat monster Gabora which ultimately leads to him conquering his own real-life Gabora, but not before becoming a local hero by nabbing two on the lam gangsters.

Honda shows sensitivity in his direction of children and has referred to this film as one of his favorites. It is a kindhearted film, promoting awareness of the loneliness faced by a generation of latchkey kids in Japan while offering solace for kids who are bullied. The stark contrast between Ichiro’s bland real world industrial landscape and his colorful fantasy land of monsters underpins the solace to be found within the imagination. I understand the reason Honda considers it a favorite in its altruistic use of Godzilla in defense of children, something adults should be able understand despite the stock footage and Ichiro’s purportedly offensive short shorts.

Of course no series featuring cinematic dinosaurs would be complete without the work of Ray Harryhausen, and the brothers chose two representative works in One Million BC (1966) and Valley of Gwangi (1969). Hammer’s One Million BC is the higher profile of the two, primarily due to Raquel Welch’s precariously tailored loincloth bikini. But the star of the film that had me convinced about the coexistence of man and dinosaurs at the age of seven is Ray Harryhausen’s parade of prehistoric delights. By this time Harryhausen had perfected his technique to the point that his animation was naturalistic, his creatures living and breathing like real amphibians and reptiles. Whether it’s a giant sea turtle or an allosaurus or a pterydactyl, the sense of unreality is confounding in the dissonance between the concrete visual input and the visuospatial cognitive process (eg one literally cannot believe their eyes). It’s an uncanny sense of wonder that is most evident in the stop-motion work of Harryhausen and his mentor Willis O’Brien, something that cannot be achieved with the hyper-real non-tactile sense afforded by the dispassionate process of CGI. Apart from its distinguished effects and longtime Harryhausen collaborator Wilkie Cooper’s evocative cinematography One Million BC plays like a silent film, its dialogue consisting exclusively of grunts and groans. Surprisingly its neanderthal gender politics are progressive as it is Welch’s character Loana who convinces brutish tribal leader Tumak to make the proper heroic decision in the end.

The other Harryhausen film in the series Valley of Gwangi (1969) was the stop-motion animator’s most ambitious as it featured over 300 animation shots, but Warner Brothers dumped it on a double-bill with a biker exploitation film and it was quickly forgotten. A broadcast television favorite of dinosaur and monster fans for decades, Gwangi’s breezy combination of classic western and “lost world” dinosaur fantasy qualifies it as ideal Saturday matinee entertainment, althought the western portion was a bit archaic even in its day in light of more revisionist entries like The Wild Bunch (1969) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). A partial explanation could be that the film was conceived some 30 years prior to its release by Willis O’Brien who wrote a treatment of a film in which dinosaurs were pitted against cowboys. Thus the film retains a nostalgic innocence that might be looked down upon as naivete today, much as Harryhausen’s work is seen as quaint or outdated. Truth be told considering the wondrous animation and compositing were all achieved by a single man, versus the weightless digital shells of today’s cartoony CGI executed by committee, there is inestimable value in the virtuosity of Harryhausen’s artistry and comfort in its affirmation of the power of human imagination. So if the film itself might not be considered exceptional as a whole, as an example of Harryhausen at his prime it is worthy of reverence. And there are elements of the film, particularly its use of sound as exemplified by Gwangi’s roars and the echoing of his footsteps during the finale in the church, that show an understanding of the craft of filmmaking in utilizing limited resources to maximal impact.

Finally a word or two regarding the progenitor of stop-motion animation cinema Willis O’Brien and his pioneering work The Lost World (1925). While there had been sporadic earlier attempts at bringing dinosaurs to life on the silver screen, including O’Brien’s own shorts The Dinosaur and the Missing Link (1915) and The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918), The Lost World was the first stop-motion dinosaur feature film forging the technique’s acceptance to a wider audience. A fast-paced adventure similar in structure to O’Brien’s crowning achievement King Kong (1933), The Lost World serves as a prime example of O’Brien’s patience and committment to the painstaking process of stop-motion in its depiction of all manner of prehistoric beasts, most notably a herd of Stegosaurus all moving simultaneously. Without the visionary work of Willis O’Brien, who served as mentor for Ray Harryhausen’s introduction to commercial filmmaking, it is difficult to imagine where the spark for popular dinosaur cinema would have originated.

Thanks to the Brothers Valaskaus for sponsoring screenings of films that are often overlooked in the theatrical realm. I would urge those who have an interest in the subject matter to attend as many of these screenings as possible to support the showing of overlooked genre efforts in a communal space where we can share in the appreciation of the innovation, warmth and creativity of handmade fantasy cinema.