Tickets at https://facets.org/CINEMA

Through the thick smog of escalating cancer capitalism during the early 1970s there was little focus on the morbidity and mortality induced by American industrial imperialism apart from a Public Service Announcement on US television featuring a (faux) Native American shedding a tear over a family littering out their car window. In Japan the recovery from World War II was embodied in unchecked industrial expansion, parallelling the US in its prioritization of growth regardless of the consequences to the public at large. Thus the revolt against corporate contamination of our water and air in both countries was synchronous in the advent of a science-fiction cinema subgenre committed to either cautioning about or expoloiting (or both) the potentially devastating consequences of our polluting ways.

Witnessing the grim reality of coastal water contimination, black smog descending upon the city of Yokaichi and a myriad of respiratory and neurological illnesses induced by heavy metal contamination of water and smog saturated air in Japan, Yoshimitso Banno wrote a treatment for Godzilla’s 11th film in which the burgeoning children’s hero would fight a transforming tadpole-like sludge monster. But Banno’s militant tone combined with his avante garde approach to filmmaking shocked longtime Godzilla producer Tomoyuku Tanaka and critics in general, all of whom found it difficult to process a personified Godzilla rubbing his nose like Japanese pop star Yuzo Kayama juxtaposed with scenes of Hedorah’s mist disintegrating agonized victims into slime-laden skeletons. Or perhaps it was the exposure of lonely latchkey kids to free-thinking counterculture and acid trip visions of fish-headed dancers and pusatile amoeboid projections that irked the adults in the room. Whatever the case there is no doubt that Banno’s film remains the most overtly radical in the entire Godzilla series and the darkest apart from Honda’s original.

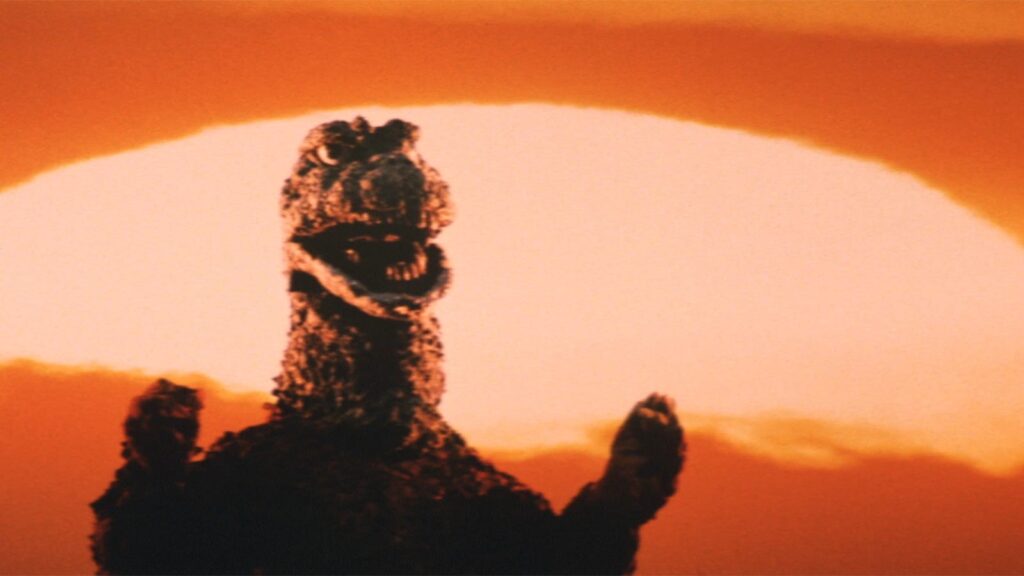

It is the most controversial entry in the series as well, being included in Harry Medved’s 1978 book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time and receiving a dumbfounded reaction from critics at the time if its release. But as someone who has looked up to Godzilla for decades (as if anyone has a choice) Godzilla vs Hedorah stands out from the rest of the Godzilla canon with the possible exception of All Monsters Attack (1969) in its lionization of Godzilla through a child’s eyes. The young protagonist Ken is first seen pushing a Bullmark Godzilla vinyl down a slide declaring his admiration for the Big G to his older brother making a statement that Godzilla is the Superman that beats them all. Godzilla’s appearance in Ken’s psyche is set against an amplified sunrise, a majestic image affirming the Big G as the savior he had become to children around the world. This messianic portrait of Godzilla is reinforced by Ken’s now famous grade school poem in which he envisions how angry Godzilla would be if he saw how humans have polluted the sea. Godzilla is indeed angry in this film, Haruo Nakajima giving his most animated performance as Godzilla, doing everything from ripping Hedorah to bits to staring down the puny humans and their incompetent military. This is indeed a Godzilla that any kid could confide in, borne out by the fact that Ken reveals to one of his Godzilla vinyls that he literally knows how the Big G feels. Perhaps part of the division in perceptions of the film represents those who do and those who don’t.

While Godzilla serves as a metaphor for nuclear destruction in Honda’s 1954 film, Hedorah is a direct representation of the envoronmental threat posed by toxic waste and consumption of fossil fuels. Hedorah is seen fracturing the hulls of oil tankers, pools of black spilling into the ocean, and in an animated sequence he lifts half a tanker above his head and guzzles its oil. In his clam-like flying incarnation, Hedorah releases a gaseous mist that chokes humans and Godzilla alike, and his acidic mist results in graphic onscreen deaths, carefully avoided in the Godzilla series up to this date apart from the original. It’s evident that Banno understood the perils posed by fossil fuels even though the climate impacts of drilling for and burning fossil fuels were not widely known until the late 1980s. Considering the urgency of the film’s message and its psychedelic deviation from the relatively innocent tone of the Showa series (apart from the original of course) the fan obsession with the absurdity of Godzilla flying has always been lost on me. Plus I found Godzilla’s/Nakajima’s pantomime of flying in preparation for takeoff to be enchanting. It certainly helps with a film like Godzilla vs the Smog Monster to be able to view it from the perspective of a child and an adult, and not from the compliant technocratic context.

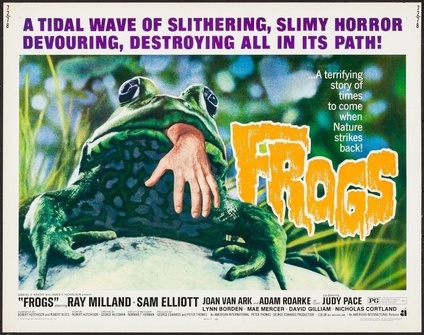

Within 3 months of the release of Godzilla vs the Smog Monster in the US, George McCowan’s Frogs (1972) was released by American International Pictures. In New York, AIP paired the two films for a long-running double-feature in 103 theatres, hardly impressing establishment film critic Vincent Canby who viewed Frogs as an “end-of-the-world junk movie” and Godzilla in Godzilla vs Smog Monster as looking “as embarrassed and pious as an elderly clergyman at a charity masquerade ball.” Not surprising for a New York Times film critic (talk about looking from the top down), but telling in that the elitist establishment was dismissive of considering grassroots cinematic activism. The joy of Frogs not in the consideration of its crafting, although Mario Tosi’s lush cinematography matches that of its locations, but in its affectione and empathy for its title amphibians and all the creepy crawlers they recruit. Sympathies are amplified for the disrespected toads (not frogs), tarantulas, snakes, lizards and arachnids by the boorish behavior of the majority of the human characters, the most notable being conservative paper mill owner Jason Crockett (Ray Milland).

As portrayed by a persuasively ornery Milland, Crockett is the epitome of a present-day Fox News watcher, completely self-absorbed and mocking of anyone expressing concern regarding the consequences of poisoning the local flora and fauna. It is no coincidence that Crocket’s birthday is July 4th as he represents the nationalist pride of colonization from his plantation estate to his greed to his racist gaffes. Other characters represent unsympathetic socialite incarnations of the Seven Deadly Sins, their demises generating an “eye for an eye” satisfaction in the graphically portrayed and visibly uncomfortable onscreen deaths. The degree of satisfaction garnered from the onscreen onslaught of ticked-off toads and galled geckos is undoubtedly directly proportional to one’s emotional investment in the welfare of such otherwise benign animals, but those with an affinity for the curious little creatures photographed through obsessive macro focus and fisheye distortion will have no difficulty believing that the sternly onlooking toads are perfectly capable of directing those geckos to release toxic gases in the greenhouse.

There is little arguing that Frogs delivers just what one would expect from a film with a marketing campaign featuring the image of a spotted frog burping up a human hand, yet for some reason the prevailing criticism remains that most of the species depicted in the film such as frogs (or toads) or lizards are not particularly deadly. Such perfunctory criticism validates the film’s perspective that we as humans are so callous in our assumed dominance to the species that support our very existence that we could never conceive of a way in which presumably benign yet ubiquitous creatures could turn against us. While it’s not surprising that we were oblivious to this possibility in 1972, it would seem that in light of the loss of 70% of our animal species over the past 50 years, including over 100 amphibian species since 2004, that nature’s vengeance might not come in the violent sense as depicted in Frogs but in the passive sense of forced mass migrations due to starvation and economic collapse due to loss of biodiversity.

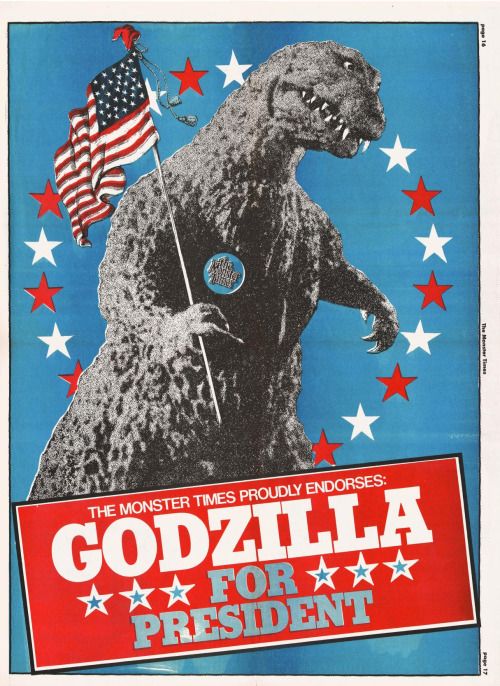

At the very least Frogs and Godzilla vs Smog Monster should have inspired some reflection upon the broader significance of two such similarly themed low-budget science-fiction films being released simultaneously, but instead the tone in critical circles was largely condescending (or in the case of Godzilla vs Smog Monster incredulous). The appreciation of these films some 50 years later is bittersweet, as in retrospect they serve as cathartic in channeling the frustration of Godzilla and a cohort of creepy crawlers attempting to save the planet because we are too ignorant to do so ourselves. I could only imagine that the real Godzilla would be very angry indeed if he saw how his warning from half a century ago had fallen on deaf ears. The amphibians on the other hand might not get the chance as 50 of their species have been obliterated since 1972. It’s high time we started taking the lead from the activist amphibians and crusading kaiju. They are at the very least more trustworthy than the monstrous leadership that feigns concern while inflicting more destruction than Godzilla ever has, so I say amphibians for Ambassador of Environmental Protection and Godzilla for President 2024.

It would be funny if it weren’t the best option.